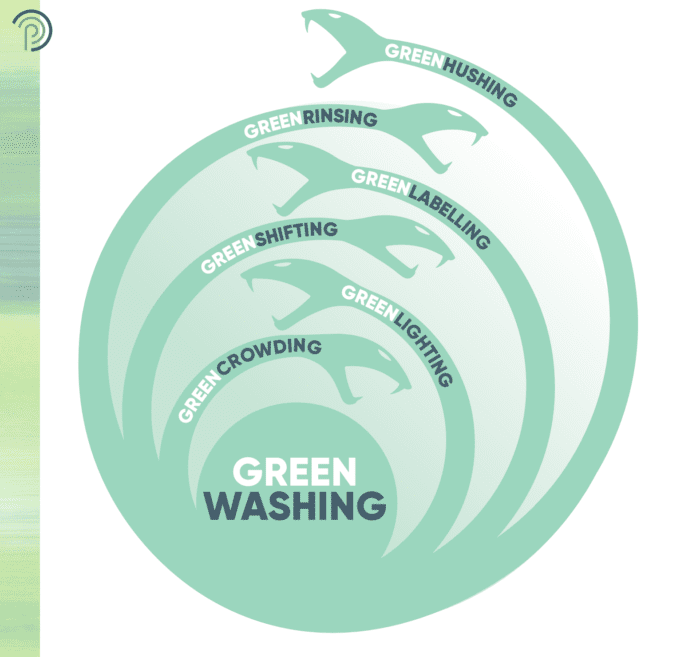

Planet Tracker’s new report, titled The Greenwashing Hydra is nod to Greek mythology where the serpentine water monster would get one of its heads cut off and grow two more. Planet Tracker sees greenwashing as a Hydra-like beast where one Greenwashing form gets cut down, only to be replaced with two new sophisticated strategies.

“There are many reasons why companies engage in greenwashing,” said the report. “It is possible for greenwashing to occur from corporate ignorance. However, a company is often incentivized to make its products more attractive to consumers, thereby increasing sales volumes and/or enabling price rises. Greenwashing tactics could achieve this. Furthermore, an increasing number of employees are attracted to work for companies with strong sustainability credentials. Companies with strong ESG credentials can attract a valuation premium relative to their peers as investment into sustainable and ESG funds increase. In turn, this can lower the cost of capital as their equity attracts a higher price and they therefore must issue fewer shares to raise funds. The same is true of green debt where investors have been prepared to accept a lower yield in return for sustainability and ESG targets. In summary, simply making a company appear more environmentally sustainable and caring appears to carry only upside, unless the claims are shown to be false. It should be remembered that making false environmental claims hinders the development of the green economy.”

In the report, Planet Tracker identifies what it calls Six Shades of Green:

Greencrowding

“Greencrowding is built on the belief that you can hide in a crowd to avoid discovery; it relies on safety in numbers,” said the report. “If sustainability policies are being developed, it is likely that the group will move at the speed of the slowest.”

An example of Greencrowding could be a group or coalition that wins a lot of support and funding, but promotes little change. The idea would be to move with the masses to avoid scrutiny and look like an advocate for progress even if the company isn’t doing anything actionable.

Greenlighting

“Greenlighting occurs when company communications [including advertisements] spotlight a particularly green feature of its operations or products, however small, in order to draw attention away from environmentally damaging activities being conducted elsewhere,” said the report.

Greenlighting is probably one of the most common forms of greenwashing we see in the press. There are plenty of examples of catchy stories that sound good but are a drop in the bucket compared to the overarching business.

To be fair, it’s common across all businesses and media, no matter the industry, to talk about interesting topics that will catch the attention of investors and stakeholders, even if they are immaterial. It’s why we are drawn to anecdotes over statistics.

As bad as greenlighting is, there are many examples of companies that may have started their ESG story with what may have at first appeared like greenlighting but then turned into material change. For example, ExxonMobil was notorious for greenwashing. It pounded the press with its 2018 algae biofuel ads even though biofuels made up a negligible apart of its business. The company was also the last oil major to pledge net-zero by 2050.

Yet to its credit, ExxonMobil announced in December 2021 that it would have net-zero Permian Basin operations by 2030. It also said that by year-end 2021, it would reduce flaring volumes across its Permian Basin operations by more than 75% compared to 2019. It hit that goal. ExxonMobil also announced that it would eliminate all routine flaring in the Permian by year-end 2022 in support of the World Bank’s Zero Routine Flaring initiative. On January 24, 2023, ExxonMobil announced that it had ended all routine flaring in the Permian Basin, that it would push for harder regulations for the region, and that it would encourage its peers to do the same.

In sum, greenlighting is widespread and needs to stop, but also companies are doing a combination of greenlighting and fostering real change. ExxonMobil’s flaring reduction efforts have been swift and effective. Maybe one day its biofuel investments will reach material benefits it had previously claimed too.

Greenshifting

“Greenshifting is when companies imply that the consumer is at fault and shift the blame on to them,” said the Planet Tracker report.

Greenshifting is commonly used in the oil and gas industry during marketing campaigns that blame the carbon impact of fossil fuels on the consumer just as much as the company. If a company implies innocence by saying it was just pumping oil and natural gas because consumers needed it to want to cool their home or fuel their car, then that would be a form of Greenshifting. Planet Tracker said that greenshifting is one of the easiest forms of Greenwashing to identify.

Greenlabelling

“Greenlabelling is a practice where marketers call something green or sustainable, but a closer examination reveals that their words are misleading,” said the report.

Greenlabelling is commonly used for consumer goods like “100% renewable plastic” or “100% recycled paper. A product or service could also be labeled as renewable or environmentally friendly through carbon offsets even if it is not.

Greenlabelling reminds me of when Kraft got in trouble for labeling its macaroni and cheese and Kraft Singles as made with “real cheese,” but then was called out for the main ingredient being a “pasteurized prepared cheese product.” The FDA allows a product to be named cheese if it’s at least 51% real cheese, so Kraft was able to get away with it. This level of greenlabelling is laughable, downright embarrassing, but painfully common.

Greenrinsing

“Greenrinsing refers to when a company regularly changes its ESG targets before they are achieved,” said the report.

Greenrinsing is one of the harder forms of greenwashing to sniff out because it requires keeping up with past and present ESG goals by reading ESG reports. At ESG Review, we’ll do our best to help you with identifying greenrinsing.

The Greenrinsing example that Planet Tracker used was from its report called Soda-pressing, which involved Coca-Cola and PepsiCo. “In Soda-pressing we revealed the frequency with which these two companies adjusted their recycling targets before the target date,” said Planet Tracker. “Instead, they pushed forward the target date while upping the previous target. Over the past five years, PepsiCo has changed its recycling targets three times, while Coca-Cola has done so twice. In addition to the ever-moving targets, both global brand owners identified an extensive number of risks on why they might not be able to meet their targets; 47 from Coca-Cola and 13 from PepsiCo. Greenrinsing demonstrates how greenwashing has become increasingly sophisticated. Its origin can be found in those companies which set ambitious targets but fail to achieve them or their rhetoric failing to match their sustainability outcomes.”

Greenhushing

“Greenhushing refers to the act of corporate management teams under-reporting or hiding their sustainability credentials in order to evade investor scrutiny,” said the Planet Tracker Report.

Greenhushing has been in the news as of late regarding ESG investing, where major asset management firms have been called out for labeling a fund as ESG friendly when in reality the paradigms of the screening were arbitrary at best. The ESG investing standards got so bad that ExxonMobil replaced Tesla in an ESG fund. Despite Tesla’s poor social and governance scores, it’s silly that on the same day Tesla was kicked out of the S&P Dow Jones Indices’ ESG fund, ExxonMobil and Marathon Petroleum were added in. In response to the news, Musk tweeted “Exxon is rated top 10 best in world for ESG by S&P 500, while Tesla didn’t make the list! ESG is a scam. It has been weaponized by phony social justice warriors.”

The cover feature of the Q1 2022 issue of ESG Review was a piece titled “The Gilded Age Of Greenwashing.” In that article, we discussed the importance of actions over words. Carbon-neutral pledges are good natured, but results speak for themselves. We’d love to see every company hit its medium- and long-term goals. The reality is many won’t. Companies shouldn’t be added to an ESG fund simply because they say they will do something. They should be added to an ESG fund only when they prove they are committed to ESG and don’t view it as a fad, but rather, an essential part of conducting a business that benefits all stakeholders and not just shareholders.

For that reason, ExxonMobil and Marathon Petroleum do not deserve to be added simply because they only began ramping up the ESG rhetoric. It’s too early. Tesla also arguably does not deserve to be included because hitting on the “E” isn’t enough.

In general, the biggest problem we are seeing with Wall Street’s interpretation of ESG is that every company wants to be included. And right now, most companies are getting their way. Financial institutions benefit from including more companies in ESG funds because it gives them an excuse to charge higher management fees for an ESG exchange traded fund (ETF) than an S&P 500 index fund.

At its worst, the ESG fund trend is reminiscent of the atrocities committed by ratings agencies during the financial crisis. Ratings agencies were arguably the biggest catalyst for widespread fraud and delinquencies because they did not do their due diligence for the mortgage bonds they were tasked with inspecting. Instead, they dished-out AAA investment grade ratings like they were candy when the underlying assets held in many of those bonds would soon become insolvent.

In sum, making an S&P 500 ESG index fund that includes the vast majority of S&P 500 components and then making an example out of Tesla is not the way to go about gaining credibility for ESG investing. Neither is adding oil and gas companies that have only recently changed their marketing campaigns and committed real dollars to work. Let’s see if those commitments turn into real projects before handing out participation trophies.

Greenrinsing and Greenhushing are closely related. If a company fails to meet its ESG targets, it could employ Greenrinsing and push back the target date, or Greenhushing to fudge the numbers in its ESG report. Although Greenrinsing and Greenhushing are two of the hardest forms of greenwashing to identity, they could both be used in exponentially higher volumes as more and more companies file ESG reports year after year and grow closer to interim ESG goals between 2025 and 2030.