On January 26, 2024, the Biden Administration announced a temporary pause on pending decisions for exports of liquefied natural gas (LNG). The response was swift. Environmentalists heralded the move as a win for planet earth, citing the benefits of reducing dependence on fossil fuels. Energy lobbyists and political pundits cried foul, claiming the decision will cost American jobs, cripple the economy, and abandon European allies who have relied heavily on US LNG since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Thanks to the insatiable appetite of the 24-hour news cycle and the fact that 2024 is an election year, the amount of misinformation being lauded as truth from both sides is immense. There is no shortage of speculation, knee-jerk responses, and political posturing. What follows is an attempt to filter out the noise. Here’s what we know.

The Pause

The Biden Administration paused approvals for pending and future applications to export LNG from new projects. During this time, the US Department of Energy (DOE) will conduct a review that will “take a hard look at the impacts of LNG exports on energy costs, America’s energy security, and our environment.”

Existing and under construction US LNG projects are not affected by the pause. Seven LNG terminals are currently operating in the United States. As many as 11 expansions could come online in the next five years.

“There’s a long runway here [for LNG projects] and we’re taking a step back and thinking, okay, let’s take a hard look before that runway continues to build out,” said White House Climate Adviser Ali Zaidi in a press statement.

“The pause will allow officials to update the way LNG proposals are analyzed to avoid export authorizations that diminish our domestic energy availability, weaken our security, or undermine our economy or the environment,” said Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm in a press statement.

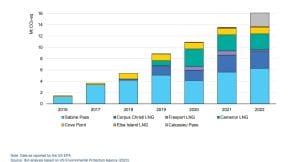

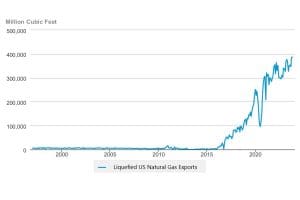

The last review of LNG export projects took place in 2018 when US LNG exports were 4 Bscf/d (113.2 × 109 m3/d). Between 2016 and 2020, the United States added more than 66 MTPA of capacity. In 2023, US LNG exports reached 12 Bscf/d (339.8 × 109 m3/d).

“The current economic and environmental analyses the DOE uses to underpin its LNG export authorizations are roughly five years old and no longer adequately account for considerations like potential energy cost increases for American consumers and manufacturers beyond current authorizations or the latest assessment of the impact of greenhouse gas emissions,” the White House said.

The Gray Area

Opponents of increased LNG infrastructure may find that the pause is less impactful than it seems at first glance. To quote President Biden’s statement, “My administration is announcing today a temporary pause on pending decisions of liquefied natural gas exports — with the exception of unanticipated and immediate national security emergencies.” Pending decisions is the key term here.

LNG projects are just as much of an organizational feat as they are an engineering marvel. There are many projects that have been approved, permitted, and received an export license, but have been delayed due to financing snags, ongoing contract negotiations between potential equity stakeholders and long-term buyers, or execution challenges like construction and procurement delays.

A good example is Tellurian’s Driftwood LNG. The project formally began construction on March 28, 2022, when Tellurian gave the greenlight to Bechtel Energy under its engineering, procurement, and construction contract. However, there’s a big difference between a ribbon cutting ceremony and dedicated, active efforts to move the project along. In the two years since construction began, Tellurian has faced numerous contract shakeups as it scrambles to find reliable buyers and sustain financing.

On February 16, 2024, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) issued Tellurian an extension that allows it to complete construction as late as April 18, 2029. The invaluable FERC extension gives Tellurian a five-year cushion to get its ducks in a row and allows it to sidestep the Biden Administration’s pause since the project is technically “under construction.”

Driftwood LNG hopes to consist of 20 trains with 27.6 MTPA of total export capacity. In recent years, delays have made the initial 2024 in-service date out of reach. Tellurian has split the project into multiple phases, with Phase 1 targeting 11 MTPA in export capacity. It’s unclear if the whole project could be exempt from the Biden Administration’s pause. Given FERC’s construction extension out to 2029, there could be a case that Driftwood LNG’s future expansions are still on the table, regardless of how long the pause lasts.

In sum, there are many projects that are grandfathered in and immune from the LNG pause because they are already approved or under construction. The United States has added LNG export capacity at a breakneck pace in recent years, but there’s still a massive amount of capacity that could come online even when factoring in the Biden Administration’s pause. The projects in Figure 1 that are under construction are unaffected by the announcement and can proceed as scheduled. However, many of the projects in the planned or proposed stages are likely affected by the pause. Notice that many of the start-up dates of the projects under construction are still years away, implying that we won’t see the full impact of the pause until after 2030.

The pause would have held far more gravity if it were announced five years ago, but a lot of progress has happened since then. FERC’s extension for Tellurian also proves the leeway that in-progress projects have, no matter if construction is active or dormant.

Decelerating Expansion Projects

Cheniere Energy’s (Cheniere) Sabine Pass Liquefaction project in Cameron Parish, Louisiana, is the largest operating LNG export facility in the United States. The facility’s sixth train entered service in 2022, bringing the total export capacity to around 30 MTPA. Cheniere is planning an expansion project for two more trains, each with 7 MTPA of export capacity, a 0.75 MTPA boil-off gas re-liquefaction unit, and two full-containment, aboveground 220,000-m3 LNG storage tanks. The project is expected to enter service in May 2029, with construction beginning in 2026.

In February 2023, Cheniere filed an application with FERC to expand the facility. On May 30, 2023, FERC accepted Sabine Pass into the pre-filing review process under the National Environmental Policy Act. On September 5, 2023, the Sabine Crossing Pipeline was added to the pre-filing review process for the project. However, because the expansion is still early into its development, it would have its export license paused as a result of the Biden Administration’s decision.

Cheniere’s second-largest project is its Corpus Christi Liquefaction plant. Train 3 entered service in March 2021, bringing the facility’s total export capacity to 15 MTPA. The plant is undergoing a 10.4-MTPA expansion, known as Corpus Christi Liquefaction Stage 3. Unlike the three larger 5-MTPA trains, Phase 3 consists of seven midscale trains. In December 2023, Cheniere said the project was 50% complete.

Cheniere has plans to add two additional midscale trains, additional refrigerant, end-flash, boil-off gas facilities, and an increase in the facility’s overall loading rates. However, this additional expansion is likely on pause due to the Biden Administration’s announcement.

Freeport LNG has been operational since 2020, consisting of three trains for 15 MTPA of total export capacity. Freeport LNG was planning to add an additional 5-MTPA train but was unable to achieve a final investment decision in 2023. The expansion’s export commencement deadline is May 2026 and may not be extended. For now, Freeport LNG Train 4 is another expansion to an existing project that is directly impacted by the Biden Administration’s pause.

Sabine Pass Liquefaction, Corpus Christi Liquefaction, and Freeport LNG are perfect examples of how operational facilities applying for an expansion are affected by the approval pause. It also shows the advantages that delayed projects have compared to those with a track record of on-time delivery. Sabine Pass Liquefaction and Corpus Christi Liquefaction have both undergone four sperate expansions, all of which have been a resounding success. And yet, Cheniere now finds itself completely stymied by the pause, unable to boost its export capacity though expansions (although it could buy stakes in projects that are having trouble getting off the ground as an interim solution). Meanwhile, projects like Driftwood LNG that don’t have an in-service date for years can carry on without federal interruption.

Emissions

To date, natural gas has helped reduce emissions by replacing coal-burning power plants. As more of these plants are decommissioned, the question becomes, how long will the coal-to-gas transition effectively reduce emissions?

A study by the University of Calgary found that LNG exports can reduce global carbon emissions only until about 2035, in a scenario where nations achieve the Paris Climate Agreement goal of limiting warming to 2.7°F (1.5°C) above preindustrial levels.1

“That’s because at that point, there simply wouldn’t be enough coal plants still operating that could be replaced with lower-emitting natural-gas power plants,” said Arvind P. Ravikumar in an article published in MIT Technology Review.2 Ravikumar directs the Sustainable Energy Development Lab at Harrisburg University of Science and Technology in Pennsylvania and co-authored the University of Calgary paper. “But if the world misses that temperature target, and most signs suggest it will, natural gas could continue to help cut power-sector emissions over a longer time period. Indeed, in a scenario where temperatures rise by 5.4°F [3°C], natural gas could still be supplanting coal through 2050 — though, to be sure, we should strive to avoid that theoretical world for all sorts of reasons.”

Ravikumar argues that coal-to-gas switching is a limited lens through which to view the future use of natural gas. “Increasingly, it will be used in other applications, including as a feedstock for heavy industries, like iron and steel, or in manufacturing of carbon-based products where natural gas is not combusted. Any calculations of climate impact made today need to reflect how US LNG will likely be used in the future, amid shifting global needs.”

University of Calgary researchers found that until 2035, 100% coal-to-gas substitution reduces global carbon emissions across all scenarios. This implies that LNG can be a viable medium-term solution to reduce coal-based power generation through a coal-to-gas substitution. The study found that an increase in LNG exports must be coupled with substituting coal with LNG to reduce emissions. When all LNG capacity is used for new electricity generation to meet growing demand with 0% coal-to-gas switching, global carbon emissions will be higher compared to the baseline scenario. Net emissions benefits can be achieved if at least 60% of LNG capacity is used for coal-to-gas substitution in the power sector.

The study reports:

2030 is the threshold year when the climate benefits of coal-to-gas switching start eroding from additional LNG emissions. Before 2030, the potential for emissions reductions is limited by LNG availability — there is sufficient global coal-based power generation to be substituted by all LNG to offset the impact of LNG expansion (surplus coal-based power generation > 0). Beyond 2030, the potential for emissions reductions is limited by the availability of coal-based power generation — the declining share of coal use in the 1.5°C pathways reduce the climate benefits of coal-to gas-switching (surplus coal-based power generation < 0). Here, available global LNG volumes exceed those required to substitute all remaining coal and the excess LNG will generate additional emissions. For the 2°C pathway, the corresponding threshold year is 2038. However, this constraint does not apply to the 3°C pathway — throughout the 2017 to 2050 study period, coal-to-gas substitution has the potential to reduce global carbon emissions. Thus, the current LNG infrastructure build-up can be considered as potential insurance against a world on a 3°C trajectory with significant coal-based power generation through 2050.

The Biden Administration’s pause starts to make sense when factoring in the study’s findings. The pause impacts projects that are still in the planning and proposed stage, or expansions that may not have entered service until the late 2020s or early 2030s. With so much additional capacity expected to come online despite the pause, a reevaluation is needed to ensure that US LNG export capacity maintains its economic and environmental benefits without spilling into excess.

Despite gas producing around 50% lower emissions than coal when combusted, there have been mounting concerns about how much methane is leaked along the LNG value chain and what this means for the emissions footprint of LNG around the world. According to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), methane is more than 28 times as potent as carbon dioxide at trapping heat in the atmosphere. Over the last two centuries, methane concentrations in the atmosphere have more than doubled, largely due to human-related activities.

The DOE is working with several countries that export and import LNG to develop a global framework for monitoring, measuring, reporting, and verifying methane leaks. In November 2023, the DOE Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management announced an international working group to advance comparable and reliable information about greenhouse gas emissions across the natural gas supply chain to drive global emissions reductions. The intent of the group is to develop a consistent framework for the measurement, monitoring, reporting, and verification (MMRV) of methane, carbon dioxide, and other greenhouse gas emissions that occur during the production, processing, transmission, liquefaction, transport, and distribution of natural gas.

The MMRV working group will create a shared global framework for estimating greenhouse gas emissions across the international supply chain for natural gas and will collaborate to develop products such as guidance, tools, and protocols for voluntary use in natural gas markets.

In December 2023, the US EPA announced a final rule that will sharply reduce methane and other harmful air pollutants from the oil and natural gas industry. All in, federal regulation, government investments, and voluntary industry action are poised to reduce US methane emissions by more than 80% by 2030, according to researchers at the University of Calgary.

LNG Capacity

In 2023, the United States surpassed Qatar and Australia to become the world’s largest supplier of LNG. London Stock Exchange Group (LSEG) data show full-year LNG export volumes from the United States hit 88.9 million metric tons, while data from Bloomberg suggests that number is closer to 91.2 million metric tons. These figures represent a 15% increase in export volumes for 2023, driven largely by the return to full production of the Freeport LNG plant that had suffered a fire in 2022.

2024 is on track to become another banner year for US LNG, despite the pause. Data from LSEG show that the amount of natural gas delivered to US LNG export plants climbed to an average of 14.9 Bscf/d (421.9 × 109 m3/d) in January 2024, up from a monthly record of 14.7 Bscf/d (416.2 × 109 m3/d) set in December 2023. December’s record topped the prior all-time monthly high of 14.3 Bscf/d (404.9 × 109 m3/d) in November 2023.

(Data Source: US Energy Information Administration)

The United States has several major export terminals under construction which will, at a minimum, double its capacity by 2030 and could triple capacity it if all projects are completed on time. These projects are not included in the pause. Capacity will increase when the first phase of Venture Global LNG Inc.’s Plaquemines LNG Terminal comes onstream this year, followed by its second phase coming online in 2026. In addition, Golden Pass LNG Terminal is expected to see its first flow in early 2025. Three trains are expected to be operational by 2026, bringing the terminal’s export capacity to 18 MTPA. Plaquemines LNG Phase 1 and 2 and Golden Pass Trains 1, 2, and 3 will bring another 41 MTPA of US exports.

Corpus Christi LNG Phase 2 could add 10.4 MTPA of additional capacity from its seven midscale LNG trains as early as 2025. Further down the line is Phase 1 of NextDecade’s Rio Grande LNG, which is under construction and expected to add 17.6 MTPA of export capacity by 2027. The first two trains at Sempra Energy’s Port Arthur LNG are expected to add 13.5 MTPA of export capacity by 2028. Glenfarne Group’s Texas LNG is a 4-MTPA facility expected to come online in 2028. Train 4 at Freeport LNG is under construction and will add 5 MTPA of additional capacity, bringing the terminal’s total capacity to 20 MTPA. If Phase 1 of Tellurian’s Driftwood project gets off the ground, yet another 11 MPTA of export capacity could come into play as early as 2027 or as late as 2029.

All told, there could be more than 100 MTPA of export capacity entering service between 2024 and 2029, even when factoring in the Biden Administration’s pause. Figure 1 showcases several other planned and proposed projects that could increase capacity even further if the pause were lifted.

With multiple terminals under construction along the US Gulf Coast, the sector is expected to grow exponentially in the decades ahead. At its current rate, research company Wood Mackenzie forecasts that LNG exports from the United States and Mexico to reach a capacity of 238 MTPA by 2050, accounting for 30% of global supply. Among the concerns prompting the pause is the need for a better understanding of the actual demand for new LNG supply in the global market. In its 2023 World Energy Outlook, the International Energy Agency (IEA) noted an “unprecedented surge” in LNG projects coming online in 2025 and on:

Starting in 2025, an unprecedented surge in new LNG projects is set to tip the balance of markets and concerns about natural gas supply. A significant new wave of LNG export facilities is under construction: 250 Bcm per year of liquefaction capacity is scheduled to start operation by the end of 2030, equivalent to almost half of global LNG supply in 2022. The United States and Qatar account for 60% of the additional LNG, with Asia as the intended market: China alone has contracted for an additional 85 Bcm of gas since 2022. The United States, which accounts for more than 90% of LNG export projects approved since the start of 2022, solidifies its position as the world’s largest gas exporter through 2030.

Energy Security

The pause will have no immediate effect on US gas supplies to Europe or Asia. In a press statement, the White House wrote:

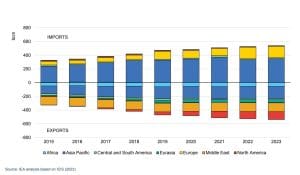

Today’s announcement will not impact our ability to continue supplying LNG to our allies in the near-term. Last year, roughly half of US LNG exports went to Europe, and the United States has worked with the European Union (EU) to successfully economize consumption and manage its storage to ensure that unprovoked acts of aggression cannot threaten its supply. Furthermore, in 2022, the EU and US pledged to work toward the goal of ensuring additional LNG volumes for the EU market – with the US exceeding our annual delivery targets to the EU in each of the past two years. Through existing LNG production and export infrastructure, the US has — and will continue — to deliver for our allies.

(Data Source: US Energy Information Administration)

The EU imported 45.6 MT of US LNG in 2023, up from 40.4 MT in 2022 and just 15.8 MT in 2021, according to data from S&P Global Commodity Insights.

In January, more than 60 European lawmakers signed an open letter to President Biden, expressing support for the pause, writing:

US LNG has played an important role in helping Europe avoid a short-term energy crisis brought on by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. At the same time almost all EU member states reduced and continue reducing their gas demand. We are concerned that a false depiction of European energy needs is now being used as an excuse by the fossil fuel industry and their allies to dramatically expand US LNG exports to the global market.

Europe should not be used as an excuse to expand LNG exports that threaten our shared climate and have dire impacts on US communities. Europe’s current consumption of fossil gas is already being met under current import levels and with existing infrastructure. Even with current demand, the European LNG import infrastructure has been used at only 60% in 2023, suggesting that there is likely no infrastructure bottleneck impeding more US LNG from reaching EU markets, and that an LNG facility build-out in the US would be even less needed. Looking ahead, and enshrined in several EU policies, European fossil gas demand is set to structurally decline as the continent continues to invest in energy efficiency and renewable energy, and to electrify its power, buildings, and industrial sectors. According to the IEA, “Europe’s natural gas demand is forecast to decline by 8% (or more than 35 Bcm) during 2022 to 2026 and by 2026 to stand almost 20% (or 110 Bcm) below the level reached in 2021.” The IEA also concluded that no new LNG infrastructure is needed to meet existing demand as we deliver on our climate pledges and work toward net-zero emissions by 2050. Combined measures set out in the RePowerEU plan could reach a reduction of -67% of the EU gas demand, compared to 2018 levels by 2030.3

Since September 2022, Russian gas accounts for only 8% of all pipeline gas imported into the EU, compared to 41% of EU imports from Russia in August 2021. Introduced in May 2022, the REPowerEU plan has diversified the EU’s energy supply mainly by establishing agreements with other third countries for pipeline imports; investing in common purchase of LNG; securing strategic partnerships with Namibia, Egypt, and Kazakhstan to ensure a secure and sustainable supply of renewable hydrogen; and signing agreements with Egypt and Israel for the export of natural gas to Europe.

Running Too Hot

While natural gas is the cleanest of fossil fuels, there is room for improvement. As an industry, we’ve made great strides in increasing efficiency and minimizing leaks, but more can be done. The rate of technological improvements alone warrants regular review of standards and practices to ensure the best measures are still being taken. In a world where consumers demand that suppliers demonstrate low methane emissions; the United States can lead the world in developing transparent and verifiable low-leakage gas supply chains.

Additionally, there is value in considering the climate impact of US LNG exports. While natural gas will remain an integral part of the clean energy portfolio for generations, emerging technologies such as hydrogen present opportunity, as well as existing solar and wind developments. As we move closer 2050, the window for limiting the impacts of climate change is shrinking. We need an all-hands-on-deck approach to solving the climate crisis. Every nation needs to develop an energy strategy that balances climate commitments, energy security, and the needs of its people.

1 Shuting Yang et al, “Global Liquefied natural gas expansion exceeds demand for coal-to-gas swithing in Paris compliant pathways,” University of Calgary, 2022

2 Ravikumar, Arvind P.: “We are having the wrong debate about Biden’s decision on liquefied natural gas,” Feb. 6, 2024, MIT Technology Review, www.technologyreview.com

3 La lettre de 60 parlementaires de toute l’Europe à Joe Biden — Justice ! (marietoussaint.eu)