Exactly one month after Enbridge announced the US$14 billion acquisition of three natural gas utilities from Dominion Energy, ExxonMobil shocked the oil patch with its proposed merger with Pioneer Natural Resources (Pioneer) in an all-stock transaction valued at US$59.5 billion. The announcement marks ExxonMobil’s largest deal since Exxon merged with Mobil 25 years ago.

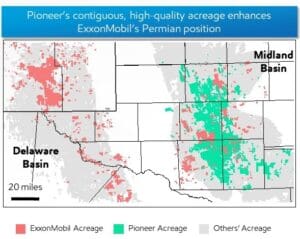

Pioneer has 850,000 net acres (343,983 ha) in the Midland Basin, making it the largest contiguous acreage of company in the entire Permian Basin. Meanwhile, ExxonMobil has 570,000 net acres (230,671 ha) in the Delaware Basin and the Midland Basin. The merger will make ExxonMobil’s Midland Basin acreage far more connected, give the company the largest share of the Midland Basin while still being a top player in the Delaware Basin, and give ExxonMobil plenty of room to ramp production across the Permian for years to come.

ExxonMobil expects its total 2027 production to exceed 5 million boe/d, with more than 2 million coming from the Permian and more than 60% of total production coming from the Permian, Guyana, Brazil, and liquefied natural gas. ExxonMobil classifies the Permian Basin as short-cycle production, whereas the other plays are long-cycle. Overall, it expects to achieve double-digit results driven by a cost of supply of less than US$35 per barrel.

Permian Production Powerhouses

2023 has been a banner year for oil and gas mergers and acquisitions (M&As), especially in the midstream industry. Aside from Enbridge’s mammoth deal, there’s the proposed merger of Oneok Inc. and Magellan Midstream Partners LP. There have also been several smaller midstream deals.

In last month’s column, we discussed the merger between Earthstone Energy and Permian Resources that gave the combined company a production capacity of more than 300,000 boe/d. The merger pole-vaulted Permian Resources to the list of the top 10 Permian Basin producers. ExxonMobil’s merger with Pioneer calls for yet another update to that list.

| Company | Permian Basin Production (boe/d) |

| ExxonMobil | 1,300,000 |

| Chevron | 772,000 |

| ConocoPhillips | 709,000 |

| Occidental Petroleum | 582,000 |

| Devon Energy | 420,000 |

| Endeavor Energy Resources | 311,100 |

| Permian Resources | 300,000 |

| EOG Resources | 277,000 |

| Diamondback Energy | 263,100 |

| Apache Energy | 212,786 |

Data Sources: Company SEC Filings, ExxonMobil October 11, 2023 Investor Presentation

Ten years ago, Permian Basin oil production was just over 1 million barrels per day (bpd), while natural gas production was around 5 Bscf/d (141.58 m3/d), which is about 1.833 million boe/d. ExxonMobil is now on track to produce a staggering 2 million boe/d by 2027 — more than the entire basin was producing in 2013.

The only thing stopping the deal from going through would be regulatory hurdles. However, ExxonMobil’s Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Darren Woods argued that the combination of ExxonMobil and Pioneer would still make up less than 15% of the region’s production, which illustrates the sheer scale of the Permian Basin’s output. It also showcases how dispersed Permian production is. Even when factoring in the consolidation from the ExxonMobil/Pioneer merger and Permian Resources’ acquisition of Earthstone Energy, the top 10 Permian producers still make up just over one half of total Permian Basin production. This puts into context the significance of smaller Permian producers, the majority of which are privately held companies.

Well Completion Improvements And Longer Laterals

So far this year, many M&A deals have been justified based on the advantages of consolidation in an increasingly competitive and diverse energy sector. Consolidation can lead to cost savings and synergies simply by removing duplications across business units. ExxonMobil expects initial synergies of US$1 billion and then US$2 billion in annual synergies over the next decade. “If you dissect where the synergies come from, roughly two-thirds of the synergies come from increased recovery of the resource as we look to apply both our technology and best practices from both companies,” said Kathy Mikells, ExxonMobil CFO on the company’s October 11 investor presentation.

In its presentation, ExxonMobil made a point to explain to stakeholders that the merger with Pioneer is an opportunity to display the advantages of ExxonMobil’s technology. This isn’t just a consolidation story, it’s a way to promote ExxonMobil’s engineering advancements and how new techniques are modernizing the oil patch.

The Permian Basin has been a hub for capital investment largely because operators have gotten so much better and producing oil and gas at lower cost. Hydraulic fracturing and horizonal drilling are key components of this efficiency. However, longer laterals are one of the biggest drivers of doing more with less. Wells are being drilled deeper vertically than ever before, but wells also have horizonal, or lateral, pipes that can extend for 2 or 3 miles (3.2 or 4.8 km) in either direction. Horizonal drilling allows a single well to achieve the coverage that 10 or 20 wells could have covered decades ago, reducing operating costs.

ExxonMobil is pushing the limits of horizonal drilling even further with 4-mile- (6.4-km-) long laterals. ExxonMobil believes that longer laterals, combined with its field digitalization and automation, will allow it to achieve a lower cost of supply, short-term cycle capital flexibility, and maximized production out of the combined acreage. “One of the challenges of very long laterals is making sure you’re getting the same productivity at the toe as you got at the heel and managing that fracturing and completion to make sure there is good productivity all along,” said Woods on the October 11 investor presentation. “We’ve come up with techniques and technologies to make sure that’s happening and measure it to make sure we’re getting the right productivity. And then, when you layer on the recovery stuff, it’s kind of a double win there. And if you then couple that with Pioneer’s acreage and the fact that they have the best acreage in the Midland Basin and you bring some of these techniques that we picked up from around our broader experience set, that is a powerful combination.”

One of the most valuable segments of ExxonMobil’s investor presentation was when Woods responded to an analyst question regarding ExxonMobil’s improved recovery rate. Woods attributed ExxonMobil’s ability to drill further than its peers to years of trial and error and understanding how to keep fractures in the shale rock open for longer. “When we first got started on this, the science was fairly immature and not well understood,” said Woods. “And what our organization has been very focused on is understanding that at a very scientific level, so that we can then trial different approaches and technologies to improve the fracturing and then keeping those fractures open. There’s a lot of work that we do around the geometry of the frac. There are many things we’re doing that are unique to the industry and delivering much better results than what we’ve seen historically and compared to many others in the industry. Understanding the subsurface and how the fractures are working leads to a different approach to well spacing. And you’ve heard us talk about the cube design and what we’ve been working on since 2018. That has gone through several evolutions as we learn and improve. The cube design continues to become more and more productive as we get better and better at understanding exactly what’s happening. You get better at recovering the resources. If you look at the cost saving side and we get better at, you know, longer laterals, faster means you can drill less wells and spend less time in the well. That improves the economics and allows you to reach out to other benches that may not be as economic with existing technologies, but then become accessible as you get more efficient and more productive. You can tap into additional resources that, without those improvements, wouldn’t be economically available.”

The Magic Wand

In 2019, ExxonMobil made the goal to produce more than 1 million boe/d from the Permian Basin as early as 2024. With the target looking increasingly unlikely, ExxonMobil pushed the goal back to 2027. However, the acquisition of Pioneer means that ExxonMobil will artificially reach its initial goal.

ExxonMobil stock is up around 80% over the last two years and 226% over the last three years, easily outpacing the performance of every other integrated oil and gas major. Today, ExxonMobil’s market capitalization is US$446 billion. Two years ago, it was US$265 billion, and three years ago, it was just US$144.2 billion. Now, you may be thinking that ExxonMobil’s rising stock price doesn’t matter unless you’re one of ExxonMobil’s happy shareholders. However, value creation at this scale is game changing for the broader industry because it effectively gives ExxonMobil a massive cash infusion that allows it to reinvest in its business, reward shareholders through dividends and buybacks, or buy out other companies.

All-stock transactions sound complicated, but they are actually very simple. The way it works is a company like ExxonMobil issues new shares of its stock and gives those ExxonMobil shares to Pioneer shareholders in exchange for all of the outstanding shares of Pioneer. The entire Pioneer business goes on the asset side of ExxonMobil’s balance sheet, while the new ExxonMobil shares go on the liability side. Because the value of ExxonMobil is about 7.5 times what it is paying for Pioneer, ExxonMobil is essentially diluting the value of each of its shares by 1/7.5, or 13.3%.

If that still sounds confusing, a simpler way of thinking about this all-stock merger is if all of ExxonMobil’s shareholders voted to sell 13.3% of the company for cash, and then used that cash to buy out all of the shares of Pioneer. Now, there are a lot of tax implications to a deal like that. The far simpler way is to propose an all-stock merger, have ExxonMobil and Pioneer shareholders pass a vote, and then exchange the shares. This way, nothing is necessarily bought or sold, it’s just traded, so there’s no tax implication unless the Pioneer shareholders sell the ExxonMobil shares they received.

Pioneer CEO Scott Sheffield is confident in ExxonMobil’s ability to create even more value for its shareholders. “This is the best company to take 100% stock,” said Sheffield in an interview with CNBC. “They have great potential with now becoming the largest Permian producer, with Guyana, with Papa New Guinea, with all their downstream capability, it’s really the best stock to own over the next several years.”

What makes ExxonMobil’s merger with Pioneer even more effective is that its stock price has outperformed Pioneer’s. For example, if ExxonMobil and Pioneer’s stock were up around the same amount over the last couple of years, then ExxonMobil wouldn’t be getting nearly as good of a deal. As mentioned, ExxonMobil’s stock is up around 80% over the last couple of years. By comparison, Pioneer’s stock is only up 32.5%. Leveraging the value of a higher stock price to buy out a company is already a powerful technique. Leveraging a higher stock price to buy a company it has outperformed makes the deal magnitudes better. If ExxonMobil had acquired Pioneer in an all-stock transaction two years ago, it would effectively be paying more than 2.5 times the price it is paying today. This bit of finance can help you understand how the rapidly rising stock price of a massive company can influence M&A throughout the entire energy sector.

ExxonMobil’s M&A relates to low-carbon endeavors as well. In October 2022, CF Industries, a global manufacturer of hydrogen and nitrogen products, entered into the largest-of-its-kind commercial agreement with ExxonMobil to capture and permanently store up to 2.2 million tons (2 million tonnes) of carbon dioxide emissions annually from its manufacturing complex in Louisiana. Earlier this year, ExxonMobil acquired carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) company Denbury in an all-stock transaction valued at US$4.9 billion. Denbury shareholders received 0.84 shares of ExxonMobil, valued at US$106.49, for each Denbury share, valued at US$89.45 per share. Meanwhile, Pioneer shareholders received 2.3234 shares of ExxonMobil, valued at US$108.89, for each Pioneer share, valued at US$253. To put these numbers into context, consider that ExxonMobil’s stock price closed 2021 at just US$61.19.

A rising stock price means that the market perceives a company to be more valuable. A company can then use that higher value and buy other companies. In this vein, ExxonMobil is growing its production capacity and investing in low-carbon solutions by simply buying other companies. It is buying those companies not through higher earnings or cash flows, but simply because its stock is worth so much more now. In a cruder sense, it means energy companies like ExxonMobil can achieve outsized profits from oil and gas, benefit from a higher stock price, and then use money made from oil and gas to fund their carbon reduction targets. It sounds capitalistic and backwards. However, the planet doesn’t care if oil and gas companies get rich, it cares about emissions reductions. If ExxonMobil steadily produces more oil and gas, but also buys CCUS companies and creates larger demand for CCUS innovation, which then leads to breakthroughs in CCUS technology and direct air capture, then the net result could still be emissions reductions.

Climate Targets

ExxonMobil plans to grow its oil and gas production at a compound annual growth rate of more than 8% between 2023 and 2027, marking the fastest expected growth rate for the company since before the oil and gas crash of 2014 and 2015. Not long ago, ExxonMobil’s production averaged less than 3 million boe/d. By 2027, it expects its production to exceed 5 million boe/d thanks to added production from Pioneer and its capital investments.

By the same token, ExxonMobil’s 2023 Advancing Climate Solutions Progress Report included ways the company is working toward supporting a net-zero future. Through 2027, ExxonMobil said it plans to invest US$17 billion in lower-emissions initiatives. In 2022, ExxonMobil reported a 10% reduction in Scope 1 and 2 emissions from operated assets compared to 2016 levels. It also reported a 50% reduction in methane intensity across operated assets compared to 2016.

In December 2021, the company announced it would achieve net-zero Permian Basin operations by 2030. It also said that by year-end 2021, it would reduce flaring volumes across its Permian Basin operations by more than 75% compared to 2019. It hit that goal. In December 2021, ExxonMobil also announced that it would eliminate all routine flaring in the Permian by year-end 2022 in support of the World Bank’s Zero Routine Flaring initiative. Earlier this year, it achieved that goal too.

In its October 11 investor presentation, ExxonMobil said that the merger with Pioneer will lower both companies’ methane emissions due to new technologies for monitoring, measuring, and addressing fugitive methane. ExxonMobil’s Center for Operations & Methane Emissions Tracking in Houston enables real-time response using methane observations from ExxonMobil’s multi-layered detection system. ExxonMobil also said that it expects to increase the amount of recycled water used in Permian fracturing operations to more than 90% by 2030.

On a per barrel basis, there is no doubt that companies like ExxonMobil are operating in a far more environmentally conscious way today than in past years. Many emissions reductions targets have been achieved in a short amount of time. Paired with an industry-wide crackdown on flaring, the oil and gas industry is cleaner than ever before. That being said, the elephant in the room is ExxonMobil’s 2050 net-zero target, a promise it made on January 18, 2022. By lowering the emissions per barrel, but increasing its overall production, ExxonMobil is effectively taking one step forward and two steps back toward reaching its net-zero target.

The Golden Ticket

ExxonMobil has repeatedly said that its specialty is manipulating hydrocarbons. This is a far different stance than other oil majors, many of which are investing in power generation and trying to diversify their portfolios away from oil and gas instead of working within the industry. In 2020 when oil and gas prices were crashing, ExxonMobil received a lot of criticism for its headstrong strategy. Today, the company is showing the market the power of working within its core competencies. ExxonMobil has one of the lowest costs of production of the oil majors. It has incredibly profitable projects and a thriving refining and chemicals business. It also remains the leader in CCUS, an area it continues to organically invest in and through acquisitions like Denbury.

ExxonMobil is creating a new blueprint for oil majors to copy. There is nothing more powerful in financial markets than a rising stock price. A few years ago, markets turned sour on oil and gas in favor of renewable energy. Today, the exact opposite is true, as markets are putting a premium on energy security. Oil and gas continues to play a pivotal role in powering industrializing economies. However, it would be a mistake to delay or not take the energy transition seriously.

As long as markets keep rewarding companies like ExxonMobil for investing in oil and gas and not renewable energy, then capital expenditures and M&A will probably center around oil and gas. It is entirely possible that ExxonMobil keeps getting bigger over the medium-term, only to flip a switch when its climate targets come under pressure by purchasing a sizeable swath of the renewable energy industry. Assuming the usual 20% or so buyout premium, ExxonMobil could theoretically buy wind giants Vestas and Ørsted, plus Siemens Energy, for around the same price it paid for Pioneer. This would never happen, but it goes to show the sheer buying power that a company like ExxonMobil has now that markets are seeing the value of oil and gas.

Today, the combined value of ExxonMobil, Chevron, Shell, TotalEnergies, BP, Equinor, and Eni is US$1.425 trillion. Three years ago, the combined value was under US$600 billion. The capital markets have waved their magic wand and created more than US$800 billion in black gold in a short amount of time. At this rate, big oil will simply counter the energy transition with M&As. ExxonMobil is the best example of this strategy playing out before our very eyes.