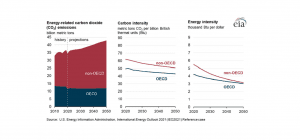

It is has become global consensus that human-caused emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) need to drop roughly 45% from 2010 levels by 2030 and reach net zero by 2050 to avoid catastrophic consequences of climate change. The US Energy Information Administration (EIA) has published its annual International Energy Outlook 2021 (IEO2021). As the planet races toward 2050 and its self-imposed emissions deadline, data from the EIA doesn’t look promising. Per the EIA report, CO2 emissions are expected to increase worldwide through 2050.

What follows in an excerpt from the EIA’s Energy Outlook 2021.

If current policy and technology trends continue, global energy consumption and energy-related CO2 emissions will increase through 2050 as a result of population and economic growth.

In the Reference case, global emissions rise throughout the projection period, although slowed by regional policies, renewable growth, and increasing energy efficiency policies, fuel choice, technology, and economic factors decrease carbon intensity and energy intensity, but they do not halt emissions growth.

Global energy‐related CO2 emissions rise through 2050 in the IEO2021 Reference case, largely driven by non‐OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries where 2050 emissions increase by 35% over 2020 levels, compared with a 5% emissions growth in OECD countries. Energy‐related CO2 emissions tend to follow gross domestic product (GDP) and population growth, which typically correlate with increasing energy demand. However, changes in the fuel mix and energy efficiency directly affect the degree to which emissions correlate with energy consumption.

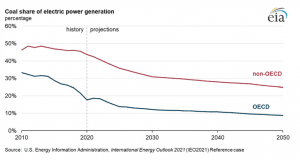

Carbon intensity and energy intensity are two useful indicators of the relationship between energy consumption, emissions, and economic activity. Carbon intensity (carbon emitted per unit of energy consumed) is largely determined by a region’s fuel mix, and it decreases in both OECD and non‐OECD countries in the Reference case over the projection period. Larger declines occur in non‐OECD Asia because of an increasing share of renewable energy, as well as technological efficiency improvements. However, the average carbon intensity across non‐OECD countries remains higher than that of OECD countries through 2050, mainly because of a higher retention of fossil fuels — particularly coal, which has a higher carbon content than other fuels. On average, the share of electricity derived from coal across non‐OECD countries is more than twice that of OECD countries over the projection period.

Energy intensity — defined here as economy‐wide energy consumed per dollar of GDP — also declines globally through 2050, and non‐OECD countries experience the fastest reductions. Although energy consumption (the numerator of energy intensity) is reduced because of energy efficiency gains, steeper increases in non‐OECD GDP (the denominator of energy intensity) are largely driving the falling energy intensity in these regions, especially in the near- to mid-term. Energy intensity between OECD and non‐ OECD countries becomes more comparable in the latter years of the projection period because technology use becomes more aligned as regional economic composition changes.

Near-term emissions reflect current policies, particularly in OECD countries, as well as GDP and population growth in non-OECD countries.

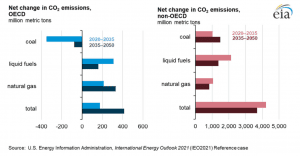

Total energy‐related CO2 emissions increase in both OECD and non‐OECD regions through 2050 in the IEO2021 Reference case. The Reference case represents an assessment of current laws and policies, including those directed at reducing CO2 emissions. Mandated efficiency, fuel, and technology goals are generally more prevalent in OECD countries. We project that net CO2 emissions across OECD countries increase by 175 million metric tons between 2020 and 2035 and then increase by more than 400 million metric tons between 2035 and 2050 because, under existing laws and regulations, government climate policies do not explicitly increase in stringency after 2030.

Energy‐related CO2 emissions grow much more rapidly in non‐OECD countries, largely as a result of increases in energy demand associated with population and economic growth. Net CO2 emissions across non‐OECD countries increase by 4,200 million metric tons between 2020 and 2035, followed by a 3,700 million metric tons increase between 2035 and 2050. The relatively slower emissions growth in the second half of the projection period is largely linked to increases in renewable energy and energy efficiency.

Emerging policy directives that are not law, such as commitments made by China’s government in 2020 to achieve carbon‐neutral status by 2060, could contribute to lower emissions in the region, but we do not include them in the Reference case because they are not specific policies.

Heavy Industry Strongly Influences Regional Emissions

Growth in heavy industries — such as basic chemicals, non‐metallic minerals, and steel — is a major component of overall economic growth in non‐OECD economies because of the rapid expansion of physical assets and infrastructure. Energy‐intensive manufacturing is difficult to decarbonize without major restructuring.

The strong growth in heavy industries in non‐OECD countries generally outpaces incremental energy efficiency improvements, leading to higher emissions in the IEO2021 Reference case. As an example, the basic chemicals industry, which has the majority of its gross output in non‐OECD countries, uses a high amount of natural gas and petroleum liquid feedstock. Reducing carbon intensity and emissions in this industry would require either a major structural shift in the production process or a shift to a more circular economy that relies less on commodity chemicals.

Similarly, the non‐metallic minerals and steel industries rely heavily on coal. Incremental energy efficiency improvements in these industries would require difficult and costly structural changes, such as employing more recycling or material substitution.

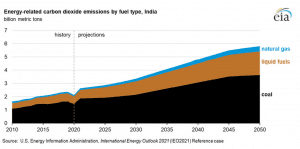

India exemplifies the role that heavy industries play in non‐OECD emission trends. India’s industrial sector is its largest consumer of coal, and the country’s coal emissions more than double over the projection period.

ABOUT THE REPORT

The EIA’s International Energy Outlook 2021 provides long‐term world energy projections.

- IEO2021 presents an analysis of long‐term world energy markets in 16 regions through 2050.

- Reference case projections in each edition of the IEO are not predictions of what is most likely to happen, but rather they are modeled projections under assumptions that reflect current energy trends and relationships, existing laws and regulations, and select incremental economic and technological changes over time.

- EIA publishes the IEO projections under the Department of Energy Organization Act of 1977, which requires that we analyze “international aspects, economic and otherwise, of the evolving energy situation” and “long‐term relationships between energy supply and consumption in the United States and world communities.”

- EIA develops the IEO using the World Energy Projection System (WEPS), an integrated economic model that captures long‐term relationships among energy supply, demand, and prices across regional markets under various assumptions.

- WEPS divides the world into 16 regions, which are generally determined based on a country’s economic size, OECD membership, location, and other factors. A region may contain one or more countries. Historically, OECD countries tend to have higher GDP per capita and energy patterns that reflect relatively more services and relatively less industrial activities within the economy, while the opposite tends to be true for non‐OECD countries.

- US projections in the IEO2021 reflect the published projections in the EIA’s Annual Energy Outlook 2021, which assumes US laws and regulations, current as of September 2020, remain unchanged.

- Energy market projections are uncertain because the events that shape the future developments in technology, demographic changes, economic trends, government policy, and resource availability that drive energy use are fluid.

The Reference case provides a baseline from which to measure the impact of various assumptions.

- The IEO2021 Reference case reflects current trends and relationships among supply, demand, and prices in the future. It is a baseline case constructed to compare with cases that include alternative assumptions about economic drivers, prices, policy changes, or other determinants of the energy system in order to estimate the potential impact of these assumptions.

- The Reference case includes existing laws and regulations, and it reflects legislated energy sector policies that can be reasonably quantified in WEPS.

- The Reference case includes some anticipated changes over time: expected regional economic and demographic trends, based on the views of leading forecasters; planned or known changes to infrastructure, both for new construction and announced retirements; and assumed incremental cost and performance improvements in established technologies based on historical trends.

- The Reference case does not include some of the following future uncertainties: changes to national boundaries and international agreements; major disruptive geopolitical or economic events; future technological breakthroughs; or anticipated policy changes as reflected in laws, regulations, and stated targets.

You can view the report in its entirety by visiting International Energy Outlook Full Narrative (eia.gov)