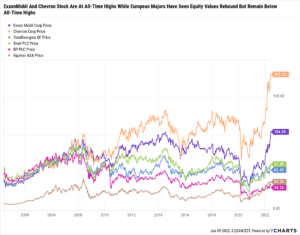

The US stock market has had one of its worst starts to the year as the S&P 500, Nasdaq Composite, and Dow Jones Industrial Average are all in correction territory. Nine out of the 11 sectors of the economy have lost value year-to-date. The two exceptions are utilities and energy. The average utility stock is up 4% as utilities tend to be recession-proof due to consistent demand. However, this gain is nothing compared to the energy sector.

At the time of this writing, the average stock in the energy sector has gained a staggering 65% so far in 2022 as eight-year-high oil and natural gas prices and strong demand has led to booming profits. Since March 2020, the average energy stock is up more than 260%.

So far, 2022 has been a perfect storm for high oil and gas prices and record energy stock prices. Despite the strong performance and pleadings from Congress and the Executive Branch, the oil and gas industry is showing little interest in ramping production anytime soon even as West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil tops US$120 a barrel. Here’s a look at the state of the industry and where it could be headed from here.

Major Recovery

In the span of a little over two years, oil and gas stock prices went from multi-decade lows to multi-decade highs.

ExxonMobil stock passed US$100 a share on June 7 for the first time in its history, marking a new all-time high. Chevron stock has more than tripled from its 2020 lows. After posting multi-billion-dollar losses in 2020, many firms across the industry are expected to achieve record-high production and profits in 2022. Some of the success has to do with how beaten down the industry was. But the main factor driving record performances and strong forecasts is the consensus decision not to boost oil and gas production even in the face of high commodity prices.

Cautiously Optimistic

There are several reasons why energy companies are hesitant to ramp production, bring more supply online, and drive oil and gas prices down.

For starters, these are the same companies that have been told for decades that they need to cut production and protect the environment. They finally listened.

In 2020 and 2021, small and large oil and gas companies alike set ambitious multi-decade environmental, social, and governance (ESG) goals. For the targets to be met, investment in low-carbon fuels like renewable natural gas (RNG) and green hydrogen must begin now.

Since profit margins are so high on US$120 WTI crude oil and US$8.30 Henry Hub natural gas prices, companies see little incentive to boost production and bring down margins — especially if the rhetoric flips in a few years and policy makers demand production to fall. Simply put, why would oil and gas companies want to give into demand needs, only to be told later that the infrastructure they invested in to boost production needs to be decommissioned?

Further Supply Hurdles

There are several headwinds preventing companies from taking advantage of higher prices even if they wanted to. It takes years to bring meaningful additional production online. If a play is underdeveloped or doesn’t have the infrastructure needed to accept new production, it can take time to secure land and mineral rights, apply for permits, build roads, lease drilling rigs, hire completion crews, and more.

Firms have their own internal goals and mid-term guidance to worry about as well. It isn’t a good look to promise investors moderate capital expenditure guidance less than two years removed from a brutal downturn, only to flip the switch and accelerate production just to capitalize on short-term trends. Unsurprisingly, firms are keeping many of their 2022 goals in-tact. However, they may be inclined to boost spending in 2023 based on how the second half of the year plays out.

In today’s environment of rising interest rates, financing is more expensive. Higher borrowing costs reduce the long-term return on investment for shale projects and larger-scale projects alike. Oil and gas companies know that these prices are likely a short-term phenomenon, so they can’t plug US$120 oil into a five- or 10-year model.

Funding projects with cash removes the need for borrowing costs. But many publicly traded firms seem to feel more inclined to use cash toward paying down debt, repurchasing their own stock, or paying higher ordinary and special dividends.

ConocoPhillips, for example, recently raised its ordinary quarterly dividend to US$0.46 per share while also implementing a variable return of cash (VROC). The VROC is meant to pass along extra profits directly to shareholders. In the company’s most recent quarter, it announced a VROC of US$0.70 per share, bringing the total dividend payment in one quarter to US$1.16 per share. Coincidently, US$1.16 per share is the exact amount that ConocoPhillips paid per share in dividends for all of 2018.

It’s also worth mentioning that supply chain disruptions continue to persist throughout the oil and gas industry. Due to the tight job market, labor costs are also much higher in the oilfield today than even just a few months ago. Many oil and gas workers left the industry during the crash of 2014 and 2015 and have continued to leave in the years that followed. Some of those workers aren’t chomping at the bit to reenter the oil and gas workforce if they have good jobs elsewhere. Supply chain challenges and the status of the labor market are two headwinds that further compress profit margins for new projects.

Incremental Increases

Chevron stock has been the best performing oil and gas major over the last 10 years. The company achieved record-high oil and gas production in 2021. Q1 2022 production was 10% higher than Q1 2021. Chevron is guiding for total 2022 production to be around 15% higher than in 2021. Yet even then, it’s not enough to meaningfully increase supply for the industry.

“We’ve seen a cycle that is frankly different than past cycles,” said Chevron CEO Mike Wirth, in a June interview on Bloomberg TV. “In the depths of the pandemic, demand collapsed at a rate we’d never seen before. Activity contracted because it had to and there was no demand for incremental production. We were looking for ways to store production that the world really didn’t need. And now we’ve seen the reverse of that in a dramatic increase in demand; economies that have largely reopened but not completely yet. We’re still seeing real strength in demand. International air travel is the strongest since before the pandemic. China still has a ways to go. So, there are a lot of signs that demand continues to be very strong and demand, typically in our industry, moves faster than supply in both directions. We saw than in 2020, and we’re seeing that today.”

Anticipating An Eventual Slowdown

The general consensus among large integrated majors, midstream firms, and oil and gas production companies seems to be that high prices could last for a few years, but that oil and gas prices are not in a prolonged uptrend because demand for oil is expected to gradually decrease in the coming decades while demand for natural gas will flatline at best.

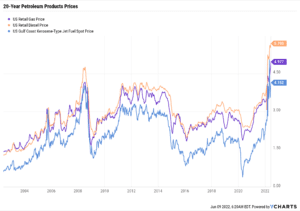

The downstream industry is particularly interesting, especially given its role in gasoline, diesel, and jet fuel production. Summer travel is booming even as jet fuel costs rise, which is contributing to inflation.

An Evolving Downstream Industry

Similar to the attitude of upstream producers toward ramping drilling activity, there’s a lack of interest in the downstream industry to commit capital to raise refinery output. “We haven’t had a refinery built in the United States since the 1970s,” said Wirth on Bloomberg TV. “My personal view is there will never be another new refinery built in the United States.”

Not only are new refineries unlikely to be built, but many oil and gas firms are divesting from traditional downstream activities toward lower-carbon fuels production such as green hydrogen and RNG.

In January, Shell completed its sale of its 50.005% interest in the Deer Park Refining Limited Partnership to Pemex for US$596 million in cash and debt. The sale is part of Shell’s Powering Progress strategy. Under the new long-term plan, Shell is consolidating its refinery footprint to just five energy and chemical parks. This will integrate the benefits of conventional fuels and chemicals production while also offering low-carbon fuels and performance chemicals. Shell said that these plants will also act as future potential hubs for sequestration.

Aside from long-term goals to invest in lower-carbon fuels in the upstream, midstream, and downstream industries, some of the hesitance for ramping investment simply has to do with the industry being roughly two years removed from one of the worst market environments in oil and gas industry. “As we were going through that very deep-down cycle where demand for fuels products dropped significantly, there was a lot of refinery rationalization,” said ExxonMobil CEO Darren Woods during the company’s Q1 2022 earnings call. “In fact, refineries were shutting down at a much, much higher rate than historical averages, four times, if not higher. And so, you’ve got this period of time where you’ve taken a lot of capacity out and new capacity that was planned or in progress has been deferred and delayed. And so, we’ve got a period with lower supply. And then, of course, as demand has picked up, that has led to this very tight market and the higher margins that we’re seeing. What’s compounded that then is the important role that Russia plays in supplying markets around the world. And with the uncertainty associated with that supply and potential impacts of additional sanctions, that’s put additional concern and anxiety in the marketplace, which is leading to a very, very high-margin environment. We’re in a bit of a very tight time frame.”

Maintaining A Favorable Reputation

Aside from the position in the current market cycle, inflation, labor costs, supply chain issues, and long-term ESG goals, one of the simplest reasons that oil and gas companies may not feel inclined to rapidly boost production to help the average American consumer is simply due to reputation. No oil and gas company wants to be labeled as the firm that got greedy and cranked up production and spread itself too thin, only to have oil and gas prices fall and look like a fool. When the market was weak, companies that were well positioned made timely acquisitions at bargain bin prices. Few companies want to choose now as the time to take on debt, lever up, and try to make as much money as possible in a short amount of time.

The high-profile companies like Chevron have a track record for keeping a strong balance sheet and taking a regimented approach to spending. Increasing production at the top of a cycle would damage that track record. “The price of oil today doesn’t influence our capital decisions and our activity,” said Wirth on Bloomberg TV. “We have a long-term view on supply, demand, markets, technology, policy, and that’s what sets our capital spending. We’ve been very disciplined with our capital spending. We’ve laid out a plan to our shareholders that stays within a pretty narrow range of capital activity. We can grow our cash flow. We can improve returns and our production will also grow. And so, we’re on that path and we’ve stayed on that path. And executing that with discipline is really important for companies like ours. And so, to deviate from that because the price today is higher than two years ago… that’s really not how we run our business. We see our way thought cycles. It’s always been a cyclical business. And so, we continue to take a longer view on how we set activity.”